A severe to profound hearing loss in both ears prevents a person from understanding speech and communicating in everyday conversations. Cochlear implants can increase hearing and communication abilities for people who don’t receive enough benefit from traditional hearing aids.

Your elderly uncle is hard of hearing and has a difficult time understanding conversation — so much so that he’s feeling frustrated and left out. His hearing aids aren’t helping much.

Your one-year-old daughter was diagnosed with severe hearing loss in both ears, and you’re worried about her ability to learn and understand speech. How will she learn to communicate?

For both of these cases, a cochlear implant may be an option.

What are cochlear implants? Who uses them and why? And how does the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) play a role? The cochlea is the part of the inner ear that contains the endings of the nerve which carries sound to the brain. A cochlear implant is a small, electronic device that when surgically placed under the skin, stimulates the nerve endings in the cochlea to provide a sense of sound to a person who is profoundly deaf or severely hard of hearing.

How Does It Work?

A cochlear implant consists of an external part that sits behind the ear and an internal part that is surgically placed under the skin. Usually, a magnet holds the external system in place next to the implanted internal system. The FDA has approved cochlear implants for use by individuals aged one year and older.

Here’s how it works:

- A surgeon places the cochlear implant under the skin next to the ear.

- The cochlear implant receives sound from the outside environment, processes it, and sends small electric currents near the auditory nerve.

- These electric currents activate the nerve, which then sends a signal to the brain.

- The brain learns to recognize this signal and the wearer experiences this as "hearing."

“A cochlear implant is quite different from a typical hearing aid, which simply amplifies sound,” says Nandkumar. “Using one is not just a matter of turning up the volume; the nerves are being electrically stimulated to send signals and the brain translates and does the rest of the work.” Moreover, cochlear implant wearers need to undergo intensive speech therapy to understand how to process what they are hearing.

Cochlear implants don’t restore normal hearing, says Nandkumar. But depending on the individual, they can help the wearer recognize words and better understand speech, including when using a telephone.

Does Age Matter?

For young children who are deaf or severely hard-of-hearing, using a cochlear implant while they are young exposes them to sounds during an optimal period to develop speech and language skills. Several research studies have shown that when these children receive a cochlear implant at a relatively young age (for example, at 18 months) followed by intensive therapy, they tend to hear and speak better than those who receive implants at an older age.

But adults and older children who have acquired severe to profound hearing loss after they have acquired speech can also do very well with an implant, partly because they are post-lingual (that is, already have learned to speak a language). “At that point, a person has to get used to the fact that what he hears sounds differently and more ‘machine-like’ than it did when he had more hearing,” Nandkumar says. “Whereas someone who was profoundly deaf at birth will adapt at a very early age to a cochlear implant and the way in which it processes sound.”

Conversely, people who are deaf since birth and have not gotten implants until they are a bit older (for example, 8 years of age) may not derive as much benefit from cochlear implants.

FDA Regulation of Cochlear Implants

Before manufacturers can bring a new cochlear implant to market, they must submit studies and data to FDA scientists, who will review the information for safety and effectiveness. Cochlear implants are designated as Class III devices, meaning they receive the highest level of regulatory scrutiny. This is because they are surgically implanted near the brain, which increases health risk. Other risks, while minimal, include injury to the facial nerve, meningitis , perilymph fluid leak (fluid from the inner ear leaks through the hole created to place the implant), and dizziness or vertigo.

The Future of Cochlear Implants

Scientists continue to look for ways to improve cochlear implants and how they function once implanted. For example:

- Companies are developing more sophisticated strategies that help to minimize background noise and increase the noise-to-sound ratio, helping the user to better focus and understand speech.

- Hearing science researchers also are looking at the potential benefits of pairing a cochlear implant in one ear with either another cochlear implant or a hearing aid in the other ear.

“A cochlear implant won’t restore hearing the way that eyeglasses can fully restore vision,” Nandkumar says. “But companies are developing increasingly sophisticated processing strategies that can reduce background noise and increase the signal-to-noise ratio, in an effort to improve the quality of speech the wearer hears.”

Before, During, & After Implant Surgery

What happens before surgery?

Primary care doctors usually refer patients to ear, nose and throat doctors (ENT doctors or otolaryngologists) to test them to see if they are candidates for cochlear implants.

Tests often done are:

What happens during surgery?

The doctor or other hospital staff may:

- insert some intravenous (i.v.) lines

- shave or clean the scalp around the site of the implant

- attach cables, monitors and patches to the patient's skin to monitor vital signs

- put a mask on the patient's face to provide oxygen and anesthetic gas

- administer drugs through the i.v. and the face mask to cause sleep and general anesthesia

- awaken the patient in the operating room and take him or her to a recovery room until all the anesthesia is gone

What happens after surgery?

Immediately after waking, a patient may feel:

- pressure or discomfort over his (or her) implanted ear

- dizziness

- sick to the stomach (have nausea)

- disoriented or confused for a while

- a sore throat for a while from the breathing tube used during general anesthesia

Then, a patient can expect to:

- keep the bandages on for a while

- have the bandages be stained with some blood or fluid

- go home in about a day after surgery

- have stitches for a while

- get instructions about caring for the stitches, washing the head, showering, and general care and diet

- have an appointment in about a week to the stitches removed and have the implant site examined

- have the implant "turned on" (activated) about 3-6 weeks later

Can a patient hear immediately after the operation?

No. Without the external transmitter part of the implant a patient cannot hear. The clinic will give the patient the external components about a month after the implant surgery in the first programming session.

Why is it necessary to wait 3 to 6 weeks after the operation before receiving the external transmitter and sound processor?

The waiting period provides time for the operative incision to heal completely. This usually takes 3 to 6 weeks. After the swelling is gone, your clinician can do the first fitting and programming.

What happens during the initial programming session?

An audiologist adjusts the sound processor to fit the implanted patient, tests the patient to ensure that the adjustments are correct, determines what sounds the patient hears, and gives information on the proper care and use of the device.

Is it beneficial if a family member participates in the training program?

Yes! A family member should be included in the training program whenever possible to provide assistance. The family member should know how to manage the operations of the sound processor.

Do patients have more than one implant?

Usually, patients have only one ear implanted, though a few patients have implants in both ears.

How can I help my child receive the most benefit from their cochlear implant?

- try to make hearing and listening as interesting and fun as possible

- encourage your child to make noises

- talk about things you do as you do them

- Show your child that he or she can consciously use and evaluate the sounds he or she receives from his or her cochlear implant

- realize that the more committed you, your child's teachers, and your health professionals are to helping your child, the more successful he or she will be

What can I expect a cochlear implant to achieve in my child?

As a group, children are more adaptable and better able to learn than adults. Thus, they can benefit more from a cochlear implant. Significant hearing loss slows a child's ability to learn to talk and affects overall language development. The vocal quality and intelligibility of speech from children using cochlear implants seems to be better than from children who only have acoustic hearing aids.

How important is the active cooperation of the patient?

Extremely important. The patient's willingness to experience new acoustic sounds and cooperate in an auditory training program are critical to the degree of success with the implant. The duration and complexity of the training varies from patient to patient.

What are the Benefits of Cochlear Implants?

For people with implants:

- Hearing ranges from near normal ability to understand speech to no hearing benefit at all.

- Adults often benefit immediately and continue to improve for about 3 months after the initial tuning sessions. Then, although performance continues to improve, improvements are slower. Cochlear implant users' performances may continue to improve for several years.

- Children may improve at a slower pace. A lot of training is needed after implantation to help the child use the new 'hearing' he or she now experiences.

- Most perceive loud, medium and soft sounds. People report that they can perceive different types of sounds, such as footsteps, slamming of doors, sounds of engines, ringing of the telephone, barking of dogs, whistling of the tea kettle, rustling of leaves, the sound of a light switch being switched on and off, and so on.

- Many understand speech without lip-reading. However, even if this is not possible, using the implant helps lip-reading.

- Many can make telephone calls and understand familiar voices over the telephone. Some good performers can make normal telephone calls and even understand an unfamiliar speaker. However, not all people who have implants are able to use the phone.

- Many can watch TV more easily, especially when they can also see the speaker's face. However, listening to the radio is often more difficult as there are no visual cues available.

- Some can enjoy music. Some enjoy the sound of certain instruments (piano or guitar, for example) and certain voices. Others do not hear well enough to enjoy music.

What are the Risks of Cochlear Implants?

General Anesthesia Risks

- General anesthesia is drug-induced sleep. The drugs, such as anesthetic gases and injected drugs, may affect people differently. For most people, the risk of general anesthesia is very low. However, for some people with certain medical conditions, it is more risky.

Risks from the Surgical Implant Procedure

- Injury to the facial nerve --this nerve goes through the middle ear to give movement to the muscles of the face. It lies close to where the surgeon needs to place the implant, and thus it can be injured during the surgery. An injury can cause a temporary or permanent weakening or full paralysis on the same side of the face as the implant.

- Meningitis --this is an infection of the lining of the surface of the brain. People who have abnormally formed inner ear structures appear to be at greater risk of this rare, but serious complication. For more information on the risk of meningitis in cochlear recipients, see the nearby Useful Links.

- Cerebrospinal fluid leakage --the brain is surrounded by fluid that may leak from a hole created in the inner ear or elsewhere from a hole in the covering of the brain as a result of the surgical procedure.

- Perilymph fluid leak --the inner ear or cochlea contains fluid. This fluid can leak through the hole that was created to place the implant.

- Infection of the skin wound.

- Blood or fluid collection at the site of surgery.

- Attacks of dizziness or vertigo.

- Tinnitus, which is a ringing or buzzing sound in the ear.

- Taste disturbances --the nerve that gives taste sensation to the tongue also goes through the middle ear and might be injured during the surgery.

- Numbness around the ear.

- Reparative granuloma --this is the result of localized inflammation that can occur if the body rejects the implant.

- There may be other unforeseen complications that could occur with long term implantation that we cannot now predict.

Other Risks Associated with the Use of Cochlear Implants

People with a cochlear implant:

- May hear sounds differently. Sound impressions from an implant differ from normal hearing, according to people who could hear before they became deaf. At first, users describe the sound as "mechanical", "technical", or "synthetic". This perception changes over time, and most users do not notice this artificial sound quality after a few weeks of cochlear implant use.

- May lose residual hearing. The implant may destroy any remaining hearing in the implanted ear.

- May have unknown and uncertain effects. The cochlear implant stimulates the nerves directly with electrical currents. Although this stimulation appears to be safe, the long term effect of these electrical currents on the nerves is unknown.

- May not hear as well as others who have had successful outcomes with their implants.

- May not be able to understand language well. There is no test a person can take before surgery that will predict how well he or she will understand language after surgery.

- May have to have it removed temporarily or permanently if an infection develops after the implant surgery. However, this is a rare complication.

- May have their implant fail. In this situation, a person with an implant would need to have additional surgery to resolve this problem and would be exposed to the risks of surgery again.

- May not be able to upgrade their implant when new external components become available. Implanted parts are usually compatible with improved external parts. That way, as advances in technology develop, one can upgrade his or her implant by changing only its external parts. In some cases, though, this won't work and the implant will need changing.

May not be able to have some medical examinations and treatments. These treatments include:

- MRI imaging. MRI is becoming a more routine diagnostic method for early detection of medical problems. Even being close to an MRI imaging unit will be dangerous because it may dislodge the implant or demagnetize its internal magnet. FDA has approved some implants, however, for some types of MRI studies done under controlled conditions.

- neurostimulation.

- electrical surgery.

- electroconvulsive therapy.

- ionic radiation therapy.

- Will depend on batteries for hearing. For some devices new or recharged batteries are needed every day.

- May damage their implant. Contact sports, automobile accidents, slips and falls, or other impacts near the ear can damage the implant. This may mean needing a new implant and more surgery. It is unknown whether a new implant would work as well as the old one.

- May find them expensive. Replacing damaged or lost parts may be expensive.

- Will have to use it for the rest of life. During a person's lifetime, the manufacturer of the cochlear implant could go out of business. Whether a person will be able to get replacement parts or other customer service in the future is uncertain.

May have lifestyle changes because their implant will interact with the electronic environment. An implant may

- set off theft detection systems

- set off metal detectors or other security systems

- be affected by cellular phone users or other radio transmitters

- have to be turned off during take offs and landings in aircraft

- interact in unpredictable ways with other computer systems

- Will have to be careful of static electricity. Static electricity may temporarily or permanently damage a cochlear implant. It may be good practice to remove the processor and headset before contact with static generating materials such as children's plastic play equipment, TV screens, computer monitors, or synthetic fabric. For more details regarding how to deal with static electricity, contact the manufacturer or implant center.

- Have less ability to hear both soft sounds and loud sounds without changing the sensitivity of the implant. The sensitivity of normal hearing is adjusted continuously by the brain, but the design of cochlear implants requires that a person manually change sensitivity setting of the device as the sound environment changes.

- May develop irritation where the external part rubs on the skin and have to remove it for a while.

- Can't let the external parts get wet. Damage from water may be expensive to repair and the person may be without hearing until the implant is repaired. Thus, the person will need to remove the external parts of the device when bathing, showering, swimming, or participating in water sports.

- May hear strange sounds caused by its interaction with magnetic fields, like those near airport passenger screening machines.

- SUMMARY:

What is a cochlear implant?

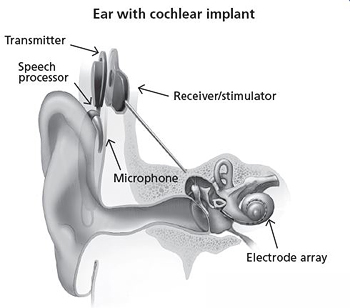

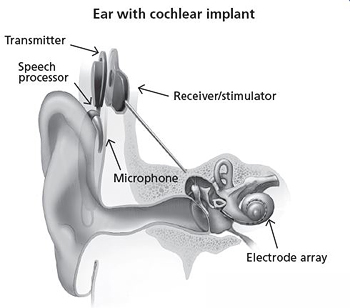

Ear with cochlear implant

A cochlear implant is a small, complex electronic device that can help to provide a sense of sound to a person who is profoundly deaf or severely hard-of-hearing. The implant consists of an external portion that sits behind the ear and a second portion that is surgically placed under the skin (see figure). An implant has the following parts:

- A microphone, which picks up sound from the environment.

- A speech processor, which selects and arranges sounds picked up by the microphone.

- A transmitter and receiver/stimulator, which receive signals from the speech processor and convert them into electric impulses.

- An electrode array, which is a group of electrodes that collects the impulses from the stimulator and sends them to different regions of the auditory nerve.

An implant does not restore normal hearing. Instead, it can give a deaf person a useful representation of sounds in the environment and help him or her to understand speech.